Leveraging federal dollars and partnership muscle to unblock legendary wild fisheries on the OP

Adult wild steelhead can be as long as your leg and weigh 20 pounds. Yet these remarkable fish have adapted to utilize habitats so small that a guppy might feel claustrophobic in them.

A case in point is Wisen Creek on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington. The “OP” is renowned for its wild steelhead and legendary steelhead fisheries, such as the Hoh, Sol Duc, Quinault and Queets rivers. Wisen Creek is a tributary to the Sol Duc and is small enough to step across in some spots.

Wild adult steelhead once spawned throughout this creek. And thanks to Trout Unlimited and our partners in a collaborative restoration effort on the OP, the Coldwater Connection Campaign—along with federal funding provided by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act—they will be able to do so again, in the near future.

Image: Luke Kelly/Trout Unlimited

Luke Kelly, manager of TU’s Washington Coast Restoration Program, is working in coastal watersheds of the Evergreen State to remove or replace decrepit culverts and road crossings and other barriers to wild steelhead and salmon migration. This spring, he is wrapping up the first phase of a project on Wisen Creek that will replace three fish-blocking culverts.

This project will improve access for steelhead and salmon to nearly two miles of quality upstream habitat and some two acres of wetland and beaver pond complex. It will also better accommodate the higher peak flows expected as a result of climate change, and improve the transport of sediment, nutrients and wood.

Image: Luke Kelly/Trout Unlimited

The Coldwater Connection Campaign, similar to TU’s Salmon Superhwy program in Oregon, is a joint effort by the Coast Salmon Partnership, Wild Salmon Center, and TU to accelerate work on the OP that reopens salmon and steelhead habitat that is currently blocked by culvert barriers.

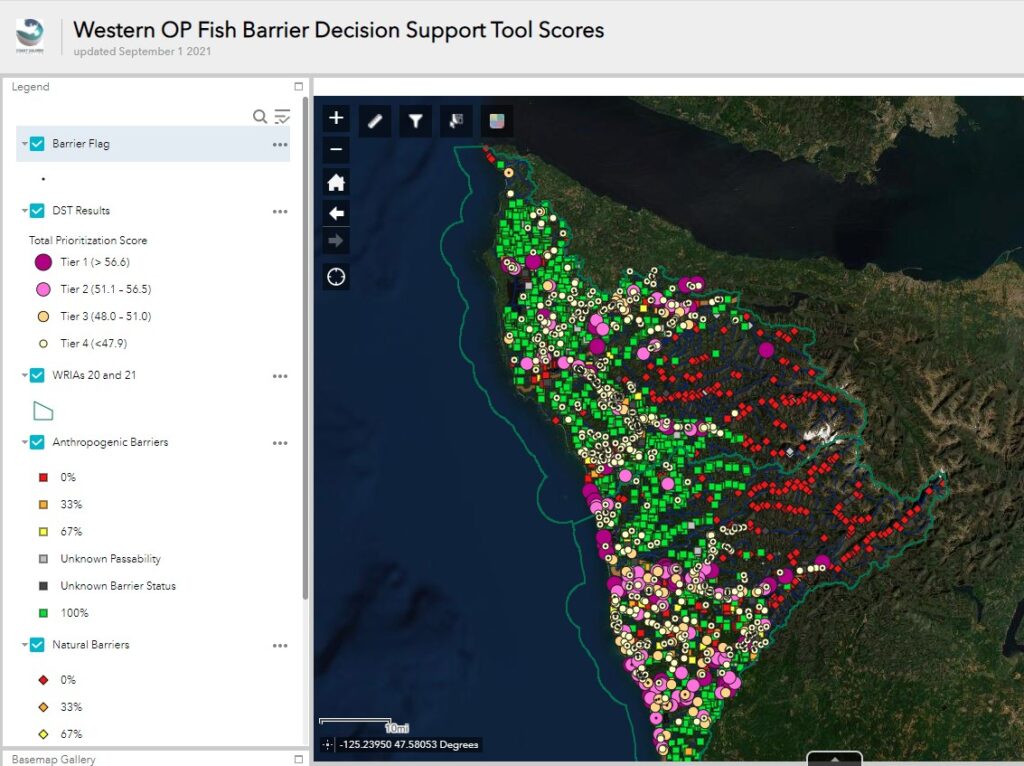

The partnership kicked off this effort by doing site assessments of more than 600 culverts. Kelly himself “walked every single mile of country road” to complete this comprehensive survey, which was key to creating a framework for coordinating culvert removal and repair efforts that can be used consistently across jurisdictions.

This technical framework, or Decision Support Tool, is built from existing prioritization methods used by various local government agencies, and includes involvement and technical input from tribes as well as federal, state, and local organizations.

TU is also a partner in the Anton & Cedar Creek Fish Passage Restoration project on the OP, which will replace two culvert barriers on tributaries to Bear Creek, an important salmon and steelhead producer in the Sol Duc basin. The work will also restore migratory access to 4.9 miles of anadromous habitat for fall Chinook, coho, chum, steelhead, sea-run coastal cutthroat, and resident trout.

The project recently received nearly $1 million in funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Fish Passage Program.

This funding “is just the beginning,” Kelly says, “and we are working with our partners to secure funding for multiple other culvert barriers in the Quillayute, Hoh, and Quinault watersheds.”

Successful restoration of wild steelhead populations and the coldwater ecosystems they inhabit requires three key ingredients: sustained funding dedicated partners, and the capacity to drive and manage the actual work.

Image: Luke Kelly/Trout Unlimited

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act—which TU helped shape and pass—calls out the importance of “natural infrastructure” to the health of watersheds and is primed to supply funding for much of this work for the next decade.

Luke Kelly and his partners, including the Hoh, Quileute and Quinault Tribes, are providing the capacity on the OP.

Go here to learn more about the Coldwater Connection Campaign, and visit this page to make a donation to support Luke Kelly’s work.