Guest authors, Logan Breshears, ODFW researcher, and Ian Tattum, ODFW district biologist, work on the John Day Steelhead Project in northeastern Oregon.

By Logan Breshears and Ian Tattum

In 2020, with help from many generous donors from Trout Unlimited and Wild Steelheaders United, the John Day Steelhead Project was able to successfully capture and acoustic tag 200 wild A-run summer steelhead at Bonneville Dam.

The money raised through the initial fundraising campaign to support this science paid for 20 acoustic tags, which enabled us to track the migrations of these fish throughout the mainstem Columbia River and up into their spawning basins and was extremely helpful in better understanding steelhead migration patterns during the 2020 migration year.

This post provides some preliminary results from the 2020 tagging effort, and it will also give you a glimpse at what the upcoming field season has in store for the John Day Steelhead Project.

Results

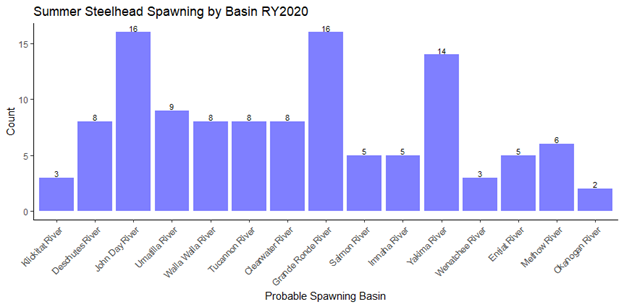

Everyone always wants to know first where all the fish we tagged in this study ended up — the figure below shows the breakdown for the probable spawning basin for each fish. Probable spawning basin was determined by using the last known acoustic tag detection, or PIT tag detection. The focus of our tagging efforts was John Day origin fish, but also fish that matched the physical characteristics of Mid-Columbia steelhead populations, and we did a good job of capturing and tagging these individuals.

We also tagged fish that were not assigned to a probable spawning basin. These fish were either possible mortalities, shed their tags, or avoided upstream PIT tag detection. Most of the “lost” fish occurred within 2 river segments. There were 29 fish lost between Bonneville Dam and The Dalles Dam (likely mortalities), and there were 33 fish lost above Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River (likely avoided PIT tag detection further upstream).

Objectives

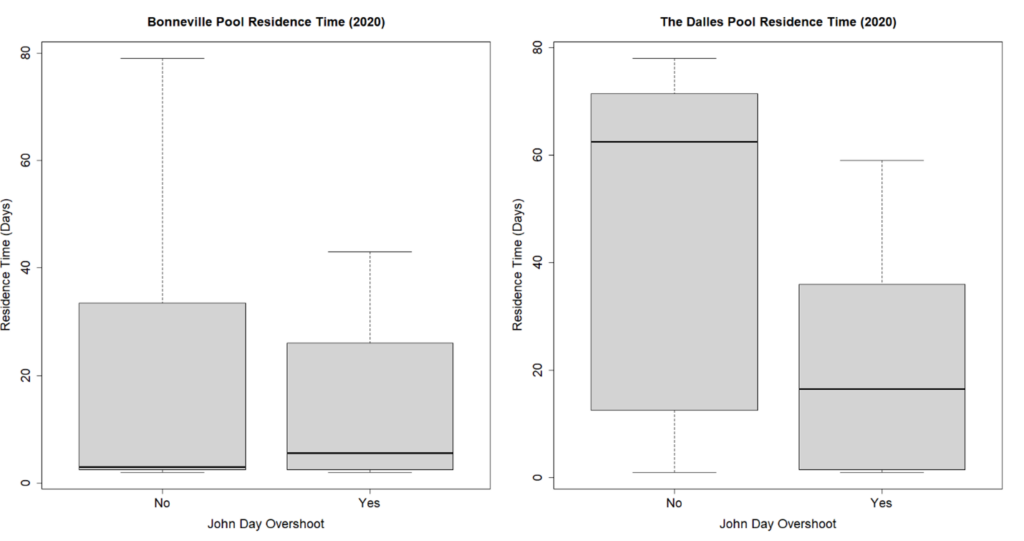

We had two main objectives for our 2020 tagging effort. Our first objective was to quantify thermal refuge usage between Bonneville Dam and John Day Dam, and our second objective was to characterize migration patterns at the confluence of the John Day River. Both aimed to improve understanding of the overshoot and fallback tendencies of John Day Steelhead over McNary Dam.

Thermal Refuge Usage

Steelhead were tracked at all of the major thermal refuge areas between Bonneville Dam and John Day Dam. Our results indicated that the most utilized thermal refuge areas were the Little White Salmon River (Drano Lake), the White Salmon River, and the Deschutes River. Fish utilized these locations for several weeks to months at a time before continuing their upstream migrations.

The dates that fish utilized the thermal refuge areas aligned well with the steelhead angling closures Oregon implemented in 2020 at Eagle Creek, Herman Creek, and the Deschutes River. John Day spawners relied more heavily on the Deschutes River for thermal refuge than other locations, and the longer a John Day spawning fish stayed in the Deschutes River, the less likely it was to overshoot the John Day River and ascend McNary Dam.

We were also able to describe a new migration strategy, in which steelhead migrated directly from Bonneville Dam to the John Day River, but would then turn around and head back downstream to thermoregulate in the Deschutes River throughout the summer months. We wouldn’t have been able to detect this migration strategy without the use of acoustic tags!

Confluence Migration Behavior

In order to better understand the migration behaviors of fish at the John Day River confluence, we installed an array of acoustic receivers that was able to project the position of a fish as it was passing through the area. We categorized fish into three groups, fish that entered the John Day River and stayed, fish that entered the river and exited, and fish that did not enter the river.

Our results indicated that most (79%) John Day spawning fish did not enter the river and stay on their first attempt. As a fish made successive attempts at entering the river, it was more likely to stay in the river, with some of these fish making upwards of four entry attempts. Most of the initial attempts were made between September and October, with successive attempts occuring slightly later in October and November.

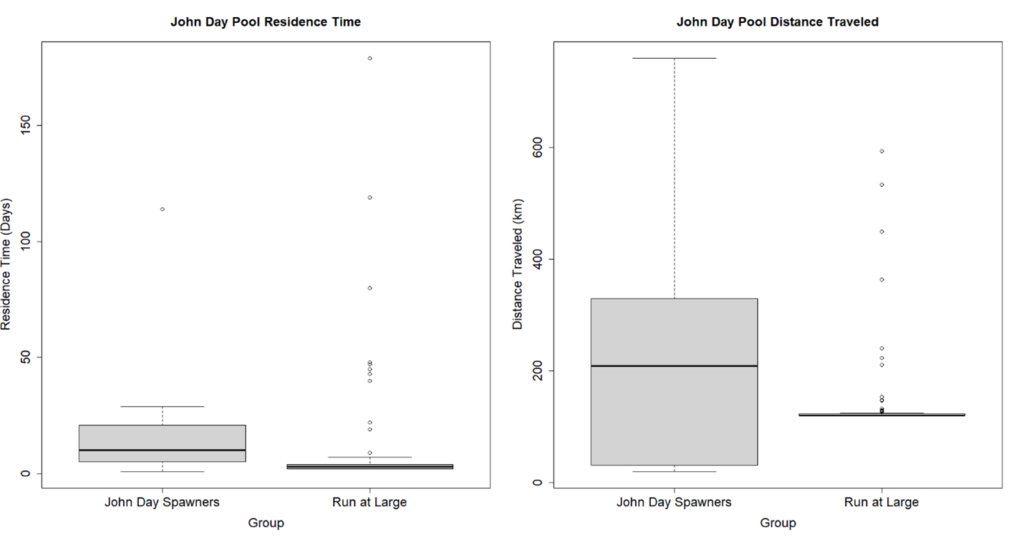

We also looked at additional migration characteristics of fish within the John Day Pool (John Day Dam – McNary Dam) as seen in Figure 3 below. We compared the residence times and distances traveled inside the John Day Pool between the John Day spawning fish and the run at large populations. On average, John Day spawners spent more days and traveled greater distances inside the John Day Pool than the run at large populations. John Day spawners only need to travel a couple kilometers inside the John Day Pool before arriving at the John Day confluence, but the median distance traveled for John Day spawners is just over 200 kilometers.

A lot of these movements for John Day spawners occurred after water temperatures in the mainstem Columbia had already peaked, implying that these fish were not actively seeking thermal refuge, and were wandering throughout the John Day Pool. In the most extreme case, we had one fish that spent 114 days and traveled 759 kilometers inside the John Day Pool!

Future Work

We are far from finished when it comes to analyzing the 2020 steelhead migration data, and we are at the stage of the analysis where we will be building more robust statistical models to accurately describe the migration patterns we saw, while also incorporating environmental variables. These models will help to drive any future management changes at the thermal refuge areas, while also providing potential management options for improving entry success into the John Day River.

In addition to all the work that was done in 2020, we have since implemented several more phases to this project. Last summer, as part of phase 2, we built and installed floating PIT tag antennas at the John Day River confluence and further upstream in the John Day arm of the reservoir. These antennas, powered by wind and solar power, were able to detect fish that same year, and provided us with the framework necessary for phase 3 of the project.

For phase 3, we will do another round of acoustic sampling at Bonneville Dam in the summer of 2022. This will allow us to do a side-by-side comparison of the acoustic antennas and the floating PIT tag antennas we installed last summer. Our goal is to develop efficiency estimates for the floating PIT tag antennas so we can transition towards using the floating PIT tag antennas in the future.

As much as we loved using the acoustic tag technology, unfortunately it’s not something we can afford to use each year. Floating PIT tag antennas will provide similar data, and the technology will be more accessible for researchers wanting to expand PIT tag coverage throughout the Columbia River.

In addition to the comparison study, we are also looking to expand our acoustic coverage into the Deschutes River to quantify the extent at which fish are exploiting that cold water resource. We are also looking to expand acoustic coverage upstream of McNary Dam to better quantify the distances that John Day overshoots are traveling.

In conclusion, the John Day River is one of the few remaining summer steelhead-bearing rivers in the Lower 48 that is undammed and not sustained by hatchery production. This project provides vital information about John Day wild summer steelhead migration characteristics throughout the Columbia River upstream of Bonneville dam, as well as their overshoot at the mouth of the John Day River. The information gathered will help impact decisions to improve the natural production of wild steelhead in the John Day River as well as other populations throughout the Columbia River basin.

For these reasons and many others, it is important that we continue to monitor and better understand these fish in order to preserve Mid-Columbia populations of steelhead, as well as the fisheries they provide for first nations, and devoted anglers alike. The more fish we are able to tag, the better we can identify key drivers behind the overshoot problem.

How can you help this effort? By donating to the project, you can help us purchase tags that will allow us to continue monitoring these iconic fish. All donations will go directly towards the purchase of tags.

On behalf of myself and everyone involved with the John Day Steelhead Project, I would like to thank everyone who contributed to our research efforts in 2020, and for your continued interest in the project going forward into 2022. This work truly could not have been done without the support from each and every one of you!

Sincerely,

The John Day Steelhead Project

Click here to donate to the John Day Steelhead Project and contribute to the purchase of new tags.