I don’t know about you, but I’m ready to put 2020 behind us. Before we do that, though, I want to shine a light on some of the rare good news we’ve had this year—again from Washington’s Elwha River.

Removing dams — even old, unproductive and unsafe ones — is never a quick or easy process (as we’ve seen over the past decade on the Klamath River). Fortunately, on the Elwha the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and other stakeholders who advocated over many years for removing the two old dams in the lower main stem eventually made it happen.

Now, I’m enjoying the fruits of their labors, specifically in my work each year with the Tribe, NOAA Fisheries, and Olympic National Park to conduct spawning ground surveys for winter steelhead and coho salmon.

Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited

I spend most of these surveys with Ray Moses, a biologist and close friend who works for the Tribe. Ray is Nez Perce; his wife Lola is Elwha; they have two young girls. Ray and I talk about the future of salmon all the time. We both want his girls’ children to have the chance to catch salmon and steelhead, just as their grandfathers were able to do in the Elwha and Clearwater and Salmon Rivers.

Ray and I have been at ground zero on the Elwha prior to, during, and after removal of the two dams. In fact, it was Ray who taught me how to implant radio-tags on adult salmon— before the dams came out. These tagged salmon were a part of a larger effort to transport some adult coho salmon above the Elwha Dam into two tributaries, Little River and Indian Creek, to help jumpstart recolonization.

Because the tributaries were not directly impacted by the sediment being released by the dams, we hoped the creeks would provide refuge for adults that could help jumpstart the recolonization process.

Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited

Ray and I were surveying together when we encountered the first coho salmon that made it to the creeks on their own accord, the first Chinook salmon, and of course, the first large male steelhead. We spent countless days tracking radio-tagged fish, sampling carcasses, and counting redds and spawning adults.

Earlier this month, almost eight years after Elwha Dam was fully deconstructed in 2013, Ray and I went out for a coho salmon survey and were struck by the number of redds we counted. In the reach we surveyed, Little River is steep and swift. There is very little spawning gravel. Nonetheless, nearly every patch of gravel that was large enough to support a redd had one. It was the highest number of redds we observed since dam removal (which spans almost two generations for the average-lived coho salmon).

A good number of coho redds were also present in the lower Little River. While the lower section of the creek is not as steep, it is still fairly confined and remarkably swift and capable of transporting most smaller trees and other debris right out into the main Elwha. Owing to the incised channel and gradient, there were almost no pools in the creek. Thankfully, the watershed has Mike McHenry and the Lower Elwha Tribe.

Mike has been working in the Elwha River basin and other watersheds on the Olympic Peninsula for over 30 years. His specialty is designing logjams to help store gravel, create more pools, and reconnect main creek and river channels to their floodplain. In the case of Little River, they had to engineer the logjams precisely because the creek runs through private property that is owned by different people. The goal was to avoid creating issues with this property, while also helping the fish.

Over the past several months Mike and his crew went to work on Little River, constructing logjams, placing boulders, and removing invasive species and planting riparian-specific native species. Tiffany Royal wrote a nice article on Mike’s work here.

Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited.

The logjams in Little River experienced their first floods this fall, and so far they are performing as expected. Pool frequency has dramatically increased, there is more spawning gravel than we have ever seen, and there is more cover for adults and juveniles. Last but not least, Little River will soon be able to access its floodplain again. The stream looks reborn, and just in time for steelhead spawning!

After the survey today, I thought: this is what I love about the nexus between science and conservation. Spending time outside with Ray. Walking the riverbanks looking for salmon. Watching the dippers. Coming to know a place intimately over several years. Seeing a creek’s fish populations take their first anadromous baby steps in over a century. And then, less than a decade later, seeing the coho salmon flourish (while this year was a crappy one for us in terms of Coho returns, the next year their offspring will have improved access to this replenished tributary.

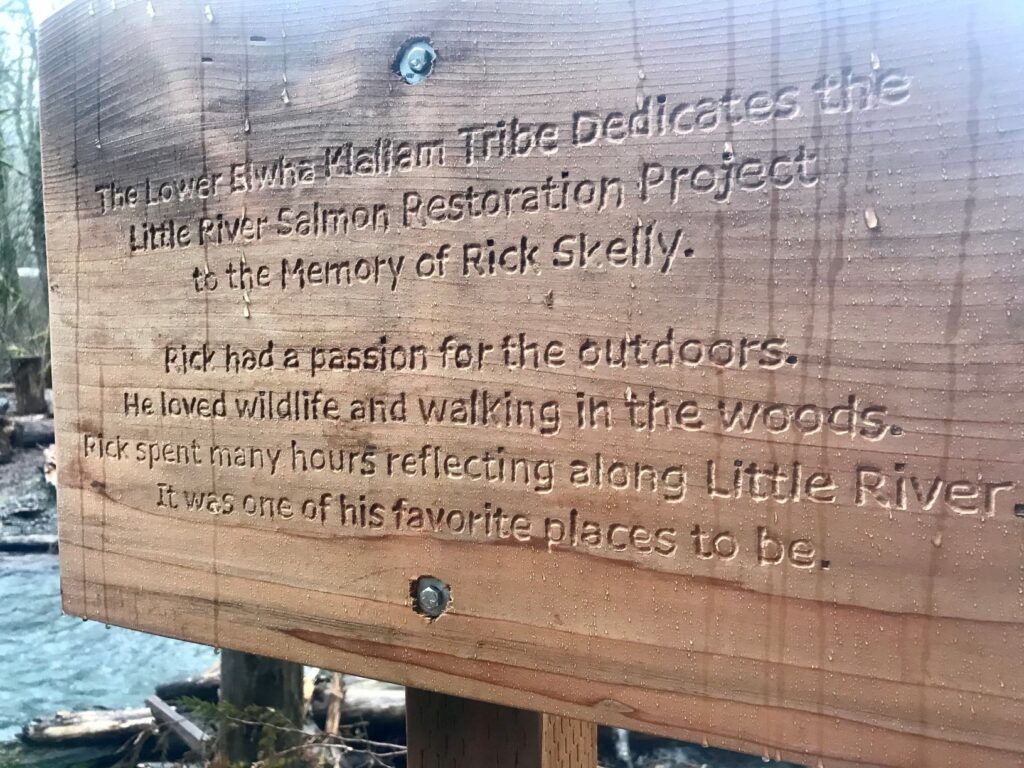

Of course, this project would not have been possible without willing landowners who allowed Mike and the Tribe to do the restoration work on their property and allowed Ray and me to conduct surveys. I want to thank the Skelly, Johnson, and Wagner families, and in particular Rick Skelly, for their strong support. Rick was a big fan of our efforts and allowed a PIT array to be installed on his property. Sadly, Rick passed away this fall and we did not get to see the project to its completion.

Thank you, Rick. Your connection to Little River will live on.