Part two: More on the new Olympic Peninsula report that looks to our past for present-day answers

We’re back with part two examining our new report, published in the North American Journal of Fisheries Management, on wild winter OP steelhead, co-authored by John McMillan of Trout Unlimited, Matthew Sloat of Wild Salmon Center, and Martin Liermann and George Pess both of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

By Geoff Mueller

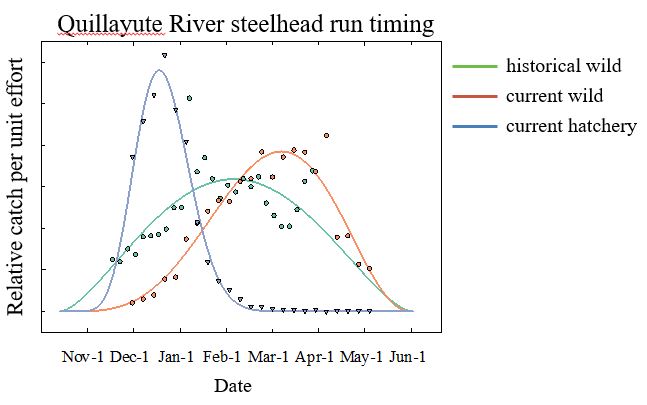

There was a time when November and December, even January, meant something more than cold fishless days on Olympic Peninsula rivers. Historical papers by anthropologists who visited the local tribes around the turn of the 20th century shed some light on the shadowy past of these early runs.

McMillan points to one document in particular that notes “January” in the Quileute language — spoken until the end of the 20th century by Quileute and Makah elders — translates to “steelhead time of entry.”

“That’s cool. It not only indicates how well these people knew their fish populations,” he says, “but also suggests winter steelhead were probably pretty important to their culture and sustenance.” As it turns out, these early returners are also important to waging a steelhead comeback on the Olympic Peninsula.

McMillan’s research on the Quillayute River, for instance, indicates that early returning steelhead often spawn higher upstream within a system, where streams are reduced in size — likely because they need higher flows to access smaller tribs that are otherwise hard to wiggle into during low spring flows. Taking that thought further, some portion of early-returning steelhead also spawn earlier, which means the spatial distribution of spawning steelhead could have diminished over time, stressing the populations’ ability to weather environmental inconsistencies from month-to-month and from year-to-year.

If condensed run timing shortens spawn timing, there’s also a scientific case for a corresponding spike in juvenile competition. Juveniles that emerge earlier redistribute farther from their redd as they grow, leaving behind vital habitat that can be filled by later emerging kin. When one group moves out, there’s now room for the next round to swoop in and take advantage of the space.

Historical (circa1955-1963) and contemporary migration timing (2000-2017) estimates based on catch per unit effort (CPUE) of wild and hatchery Winter Steelhead in the Quillayute River.

“In this way,” McMillan says, “a broader spawn timing allows more fish to stagger the use of the same habitat for mutual gains — increasing their overall productivity. It’s basically similar to how we have multiple lunch times in large schools to feed a large number of children in an efficient, timely manner.”

Lastly, having early returning steelhead in a given system could improve that population’s ability to navigate climate change. Like the rest of the world, the Olympic Peninsula will become warmer in the coming decades, and in more southerly areas winter steelhead typically enter and spawn earlier, so their juveniles can emerge before the onset of low, soupy, deoxygenated summer flows.

Rebuilding early returning steelhead life histories would help ensure that OP steelhead have the capacity to respond and adapt to unfolding ecosystem changes. Looking long term, it also implies that early returning steelhead, the fragile few that remain, could make up the majority on an increasingly balmy planet. In other words, rebuilding that stock makes good sense. Making it so, however, will take some work.

“From a habitat standpoint, we need to better understand where and when early returning steelhead breed,” Sloat says. And that habitat, which is partly located outside the National Park, will need to be restored. “There is some evidence that early steelhead prefer smaller streams for spawning — and these streams may have been hit especially hard by past logging.” From a fisheries and hatcheries POV, overhaul is the answer because early-returning hatchery stocks present a tough scenario for a wild fish minority forced to duck and dodge a worm and gear gauntlet en route to their baby-making haunts.

Whatever it takes, human compromise is key. And McMillan sees large-scale experimentation as the best way to prove out scenarios and find common ground between opposing interests. For instance, picture two OP rivers running side-by-side programs where early season hatchery plants remain the constant in one population, while wild fish are left to reseed bygone timeframes in another. Monitor, record, repeat. Let the fish be the determining factor.

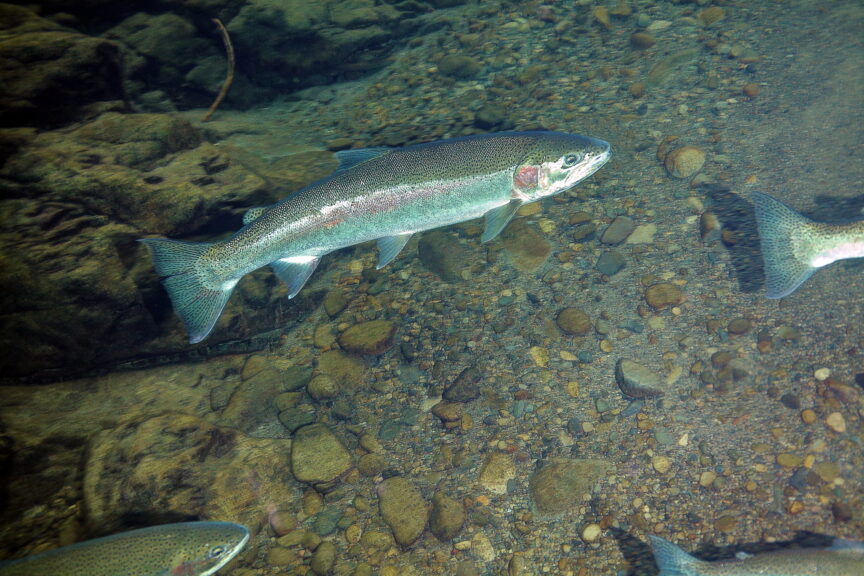

Above: Adult steelhead set for release. Image: Dr. Matthew Sloat/Wild Salmon Center

At this point there’s not much more to lose, and plenty to gain. In the end, such an effort would take cooperation from WDFW and tribal co-managers — plus the willingness of both parties to acknowledge a past that up till now had been deleted from recent memory. Only then can we put the potential of wild winter steelhead into perspective and, better yet, a plan into action.

“Rebuilding isn’t easy. Regenerating political will is hard. And it’s painful to see that we’ve lost these fish,” McMillan says. “But that pain is offset by the hope and understanding this paper provides … and that maybe now we can somehow deal with these problems and change the outcome for the better.”

Tomorrow, we continue with part three, where McMillan will provide a deeper dive into their research and findings, and explain about the lessons learned and applications for management moving forward.

Read part one in our series, The Undeleted Steelhead Decades, here.

Partial funding of this research and study was made possible in thanks to the generosity of the Wild Steelhead Coalition. Visit wildsteelheadcoalition.org for more information on their work and efforts on behalf of wild steelhead.

Geoff Mueller is an editor, writer, creative director and steelheader. Reared in the fertile waters of British Columbia, he now splits his time between chilling with his fishy wife, Kat, in Fort Collins, Colorado, living part-time in a camper near a river in Dutch John, Utah, and migrating seasonally to Pacific Northwest nooks to get lost in the ferns — casting, stepping and fishing for answers.