Do we have the fortitude to make necessary changes?

Balancing angling opportunity and conservation is never easy. Especially when fish populations are in decline and demand for fishing opportunities is on the rise.

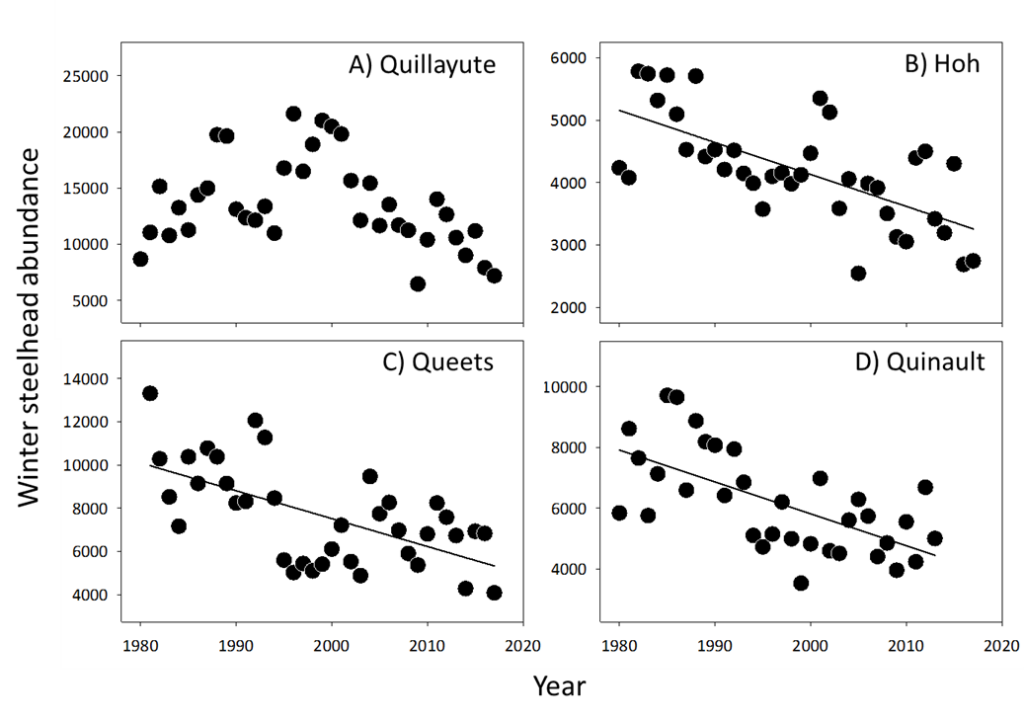

In Washington, co-managers of coastal winter steelhead fisheries are faced with that difficult task this year. On the west end of the Olympic Peninsula, wild winter steelhead populations in the Queets, Quinault, Hoh, and Quillayute River watersheds are seeing variable rates of poor adult returns, in addition to being in long-term decline (Figure 1).

Images: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited

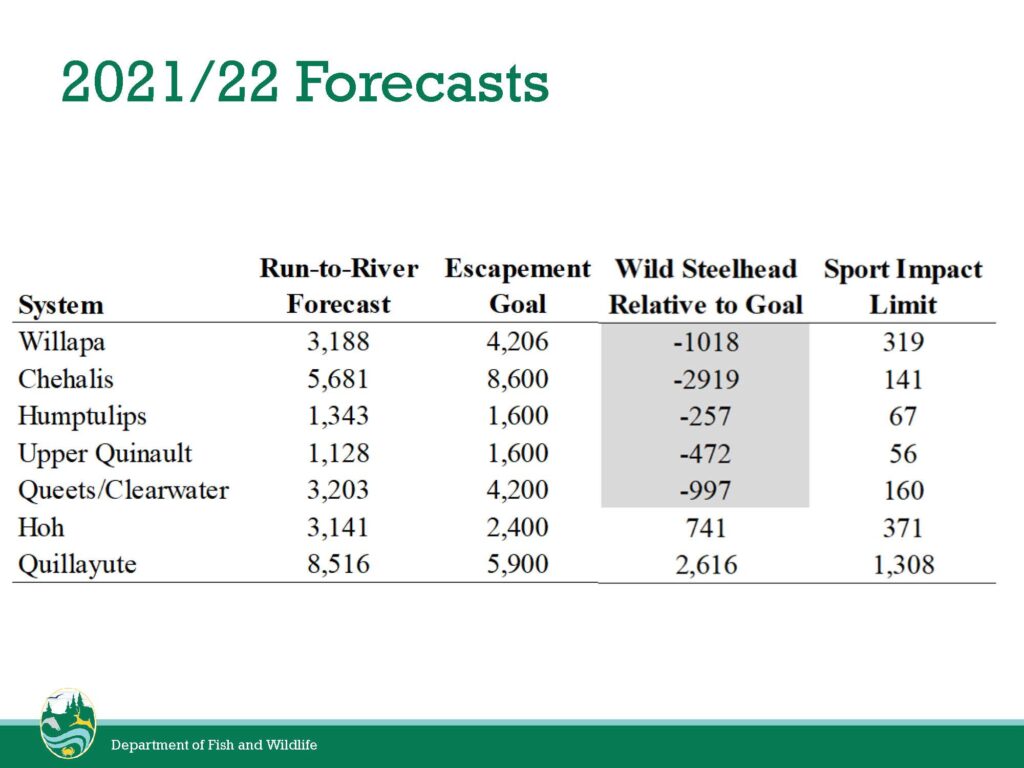

The Quillayute and Hoh returns are forecast to sufficiently exceed escapement goals to allow for recreational fishing seasons, while the Queets and Quinault run sizes will be too low to allow any recreational fishing this year (except for the early winter tribal-run hatchery fishery on the Salmon River proper in the Queets basin – see fishing emergency regulations) (Figure 2).

Image: WDFW

The new normal

While we have experienced declines in winter-run wild steelhead stocks before, as well as changes in regulations, this is different.

Think about the historic heat wave in the Pacific Northwest this summer – it was so hot mussels and other molluscs literally cooked in the tidal zone. Then there were catastrophic floods in November. The ebb and flow of warm water intrusions into the normally cold North Pacific has been happening more frequently and causing more impacts on marine and anadromous species.

The world’s ocean currents, which drive circulation of water in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, are shifting in response to climate change, sometimes wildly swinging the pendulum of survival on an annual basis and differing substantially among species and stocks.

This makes it more difficult to forecast this winter’s steelhead returns, which is one reason to be conservative with our steelhead fisheries.

Image: John McMillan

It’s not just about the ocean, however. Freshwater habitats are also changing.

Since 1980 there has been a loss of 82 glaciers and a 34% decrease in combined glacier area in Olympic National Park, which harbors the headwaters of glacially-fed rivers like the Hoh and Queets.

Further, during the past decade the OP has experienced periods of abnormally warm weather during the spring. For example, water temperatures in early- to mid-May of 2019 in the Sol Duc and Calawah rivers consistently exceeded 55°F. May 8 was the warmest day, with an air temperature of 83°F and peak water temperature of 61°F in the Sol Duc River. The main-stem Quillayute, through which all smolts must pass, was even warmer.

May water temperatures were also warm in 2018, though the heat didn’t start as early in the season.

May is an important month for steelhead smolt timing, and research indicates that smoltification is impaired when water temperatures reach 53-59°F. It’s impossible to say what the effects were and how many fish were impaired, but smolts that migrated through those warm temperatures in 2018 and 2019 are fish that would contribute substantially to this year’s returns in the Quillayute basin.

Climate change and its impacts – drought, floods, hot oceans, and generally unpredictability of frequency and intensity of weather, drought and wildfire – are here. It’s the new normal.

Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited

Uncertainty in fisheries after worst summer on record

What happened across much of the West Coast this summer could manifest itself this winter.

No one forecast the dramatic decline in summer steelhead in the Columbia River this year. Runs were expected to be poor, but not 71,000 fish poor, with only 25,000 being unclipped (wild). Nor did anyone predict steelhead to become scarce in British Columbia’s Skeena River basin – historically one of the most productive watersheds for wild steelhead in the world.

Steelhead, along with fishery managers and anglers, are, as they say, in uncharted waters.

What should be done in such years to give our wild steelhead populations the best chance to persist?

Keep fishing under current status quo regulations? Reduced or restrictive and shortened seasons? Full closures?

Considering the water temperatures in 2018 and 2019, wildly varying marine conditions, and the long-term decline of stocks in the Hoh, Queets, and Quinault rivers, Wild Steelheaders United supported a full closure of steelhead fisheries this year on the OP.

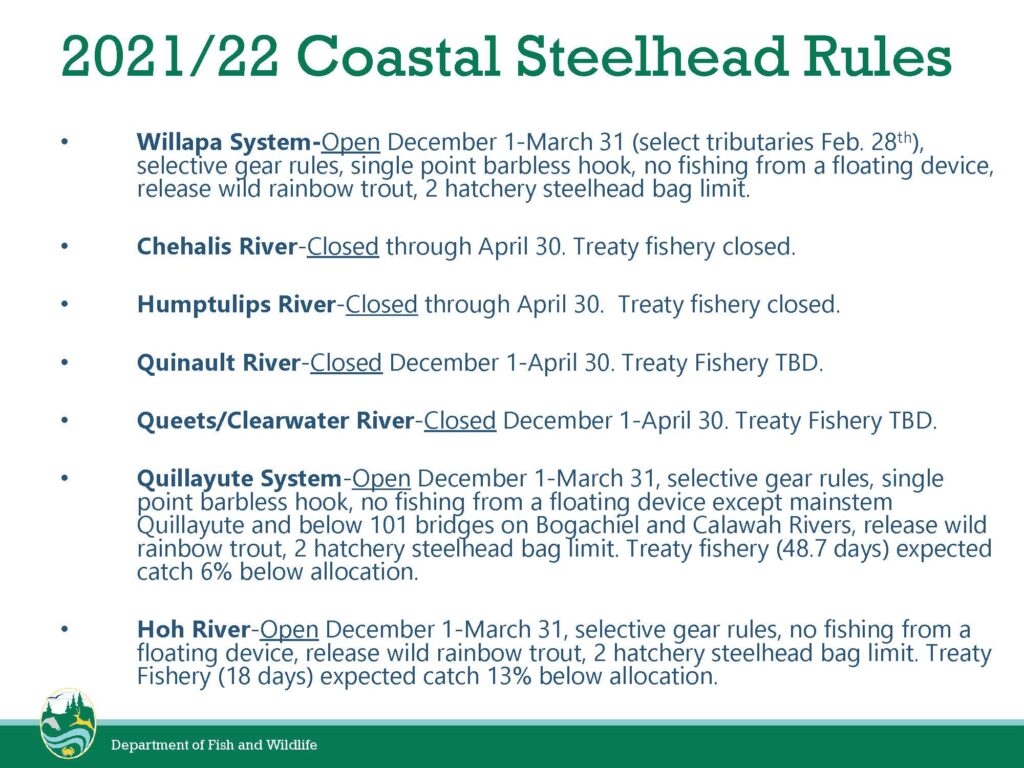

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) didn’t go that far. WDFW decided to close the Queets and Quinault Rivers and implement a restrictive, shortened season in the Hoh River (Figure 3). The season will also be shortened by one month in the Quillayute, but fishing will be allowed from boats below Highway 101 in the Bogachiel and Calawah rivers, and in the main-stem Quillayute, while fishing from boats will not be allowed in the Sol Duc, Dickey, and upper Bogachiel and Calawah rivers above Highway 101.

Olympic National Park (ONP), which manages steelhead fisheries within the Park boundaries, also closed the Queets and Quinault rivers on December 1, with a small section of the Salmon River open until January 1. Unfortunately, ONP managers did not align their steelhead fishery regulations with WDFW for the Bogachiel and Hoh rivers. Those sections of water within the Park boundary will remain open through April 15, almost two weeks past the WDFW closure of March 31.

Image: WDFW

Although Wild Steelheaders suggested a full closure after learning more from WDFW about last year’s forecast and actual run, and about the adult return forecast for this season, we have long believed it is possible to sustain fishing opportunities while making progress toward recovery of wild fish stocks. We can thus support limited fisheries in the Hoh and Quillayute, as these rivers are forecast to be over their escapement goals. . However, allowing fishing from boats – even to harvest hatchery fish – is not erring on the side of caution. Allowing fishing from boats will increase encounter rates, all else being equal, and that is the last thing that we should be striving for during poor returns. Our margins for mistakes this year are razor thin.

Maybe the fish and WDFW get lucky, and the margins hold up. Maybe they don’t, because the run sizes were over-forecast by 20%, resulting in a failure to meet the escapement goals.

The uncertainty is the bugaboo.

A long history of concern

To be clear, current WDFW staff are not to blame for the long-term decline of wild steelhead on the OP. They are, however, tasked with managing the fish and the fishery during the toughest times on record.

We applaud some of the Department’s efforts in this regard – especially their public outreach, which helped anglers better understand the data and the rationale for various management options. The public engagement by the department this year was really the first time WDFW has connected with the public on this level while adaptively managing steelhead fisheries.

Nonetheless, given the status of wild steelhead stocks on the OP, there simply is no room for mistakes. The State of Washington has a history of managing wild steelhead to the point of ESA listings, fishery closures, and frustrated anglers. We don’t want to see the same thing go down on the Olympic Peninsula.

Until we see WDFW come up with a long-term management plan for wild steelhead that includes a clear vision, goals, and actions to reverse the declining trends and rebuild the depleted early-returning component, we will continue to advocate for a very conservative approach to steelhead fishing regulations.

Image: John McMillan/TU

That is why we greatly appreciated former WDFW Commission Chair Miranda Wecker’s tough response to the OP steelhead crisis back in 2016, when she said, “The North Olympic rivers represent our last remaining stable stocks of wild steelhead. I, for one, do not want to be part of running these stocks into the ground.”

That said, we shouldn’t even be in this position, or more specifically, the fish shouldn’t be in this position. There is a longer history to declining steelhead runs than most realize.

A report by WDFW drafted as part of the Boldt Decision hearings in 1975 reveals the extent of the challenge. Among other noteworthy statements, it says of the Queets River, “A serious declining trend has been evident since 1972…. these steelhead stocks [referring to all OP populations] need substantial protection.” And that was before the Clearwater River basin, the largest tributary to the Queets, was logged as part of an experimental state forest.

Further, the report suggests, “There is a general trend toward declining salmon and steelhead stocks…. Reasons include environmental degradation and changes in harvest patterns and rates of exploitation.”

Fish and fisheries need a long-term plan

We can’t correct mistakes of the past – but we can learn from them and avoid repeating them. We must do everything in our power right now to help wild steelhead, such as altering our fishery and hatchery practices, while simultaneously working on longer-term solutions that restore and reconnect their habitats.

But these efforts need to be aligned.

The OP has a strong foundation of pristine habitat in the Olympic National Park. And there has been ongoing work, including efforts by Trout Unlimited staff, to reconnect fragmented habitats, improve riparian conditions, increase large woody debris, and decrease delivery of sediment in areas adjacent to and downstream of the park.

But if we have learned anything, it’s that climate change-related effects are manifesting faster than anticipated and fish are struggling to keep pace. Until all functional or potentially-functional wild steelhead habitat has been restored and becomes fully productive, we all must do whatever we can to help wild populations of winter steelhead on the OP persist.

Image: John McMillan/TU

And there, as Shakespeare noted, is the rub. Does WDFW have the resources and leadership to learn from the mistakes of the past and forge a new path away from ESA listings and eventual fishery closures?

It is easier to call for change from outside, of course, than it is to actually develop and implement species and fishery management plans appropriate for our current reality. Charting a new path forward will require more proactive efforts founded in strong science and policy – and collaborative engagement with the steelhead angling community.

This is, in our view, why anglers need to support WDFW’s efforts to develop a long-term plan for OP winter steelhead. The agency has taken steps – including restarting the Coastal Steelhead Advisory Group (WSU participated in the previous group and process back in 2015), hiring a quantitative modeler, and, most importantly, making necessary, adaptive adjustments to angling regulations the past two years.

WDFW and tribal nations have taken steps to address the impact of fisheries on wild steelhead populations – we applaud this progress. But substantial hurdles remain, such as agreed-upon escapement goal in the Queets, revisiting current escapement goals, the loss of early-timed winter runs, limited entry for guides, and a sustainable fisheries and hatchery framework.

It is late in the game. Olympic Peninsula wild steelhead stocks are at the proverbial tipping point of an ESA listing. Getting from depleted stocks and fishery uncertainty to more abundant and diverse stocks with more fishery certainty will not be possible unless there is a true commitment to recovery – by WDFW, Tribes, and the angling community alike. Our future fishing privileges lie in the balance.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll be sharing more about what it means to be a steelheader under these regulations, including some guest perspectives from those in the guide industry.