An ESA petition to list Olympic Peninsula steelhead has been delivered to the Feds

The news is spreading quickly among steelhead anglers and conservationists concerned about the status of Washington Coast wild steelhead populations: A long-anticipated petition to list the Olympic Peninsula’s wild steelhead under the protections of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) has been submitted to federal agencies by representatives of The Conservation Angler and the Wild Fish Conservancy (Read The Conservation Angler blog post and the Fall issue of The Osprey to learn more).

The 164-page petition was filed on August 1st. The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has 90 days to review the submitted documents and accompanying materials to determine if the petition will be allowed to proceed through the formal administrative process. If considered warranted, extensive evaluation and public comment periods will follow over the course of subsequent months before a final listing is established or declined. The complete process could take up to two years to complete.

The geographic scope of the petition includes all the watersheds contained within the Olympic Peninsula Distinct Population Segment (DPS), a region of the Washington Coast spanning from Neah Bay south to the Copalis River, including all the streams entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca west of the Elwha River. Of course, this DPS is home to iconic North Coast steelhead rivers like the Sol Duc, Bogachiel, Calawah, Hoh, Queets, and Quinault.

The petition concerns both winter and summer wild steelhead populations. It is the first ESA petition concerning Washington wild steelhead since the rivers of the Puget Sound DPS were listed as Threatened in May of 2007.

A Shock to the System, but Not a Surprise

Undoubtedly, a listing under the Endangered Species Act would have far-reaching impacts on the recreational and tribal fisheries, hatcheries, and management affecting the Olympic Peninsula’s wild steelhead, but unfortunately, the arrival of this petition should not surprise anyone who has been paying attention.

For years, anglers, advocates, and conservationists warned that an ESA listing would be inevitable if fishery co-managers did not take the necessary steps to restore the region’s declining wild steelhead populations. While the Olympic National Park has often been the region’s leader in protections for wild steelhead within their boundaries, State and Tribal fishery co-managers have been slower to respond to declining runs or even acknowledge the problems affecting populations.

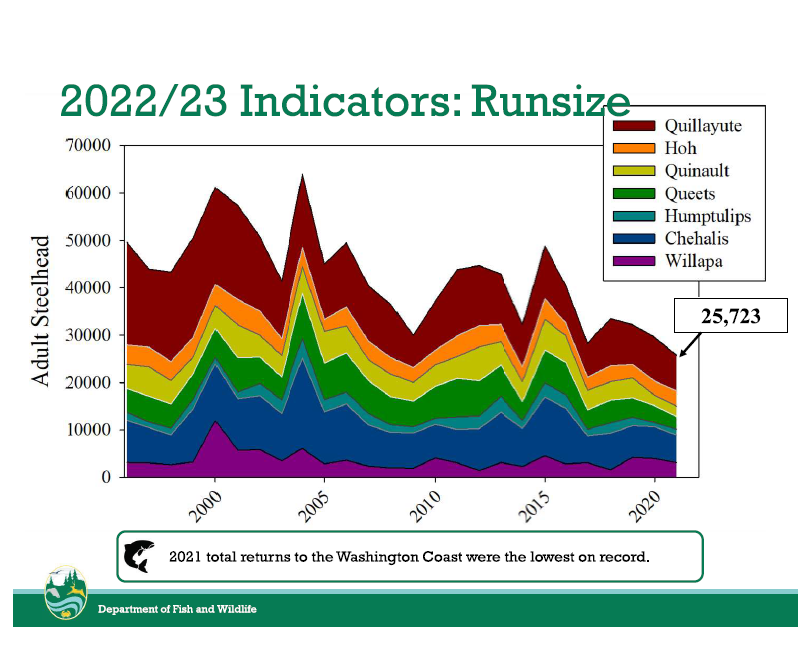

Following years of declining returns, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) managers have finally admitted in recent town halls and Commission meetings that wild steelhead populations are dangerously low. Many watersheds have been frequently missing their escapement goals for far too long. Anglers and tribal fisheries have seen shortened seasons, unprecedented closures, and emergency regulations because of historically low wild steelhead runs.

Adding to the public’s understanding of the situation, new peer-reviewed research recently published by Trout Unlimited, Wild Salmon Center, and NOAA scientists demonstrate just how far these populations have been allowed to fall, and how much peak run-timing has changed as a result of losing the early-returning winter fish. Likewise, though often overlooked by managers and the public, wild populations of Olympic Peninsula summer steelhead have nearly disappeared.

The ongoing loss of the Olympic Peninsula’s wild steelhead is an especially bitter pill, largely because it could have been prevented if managers had acted more proactively, consistently, and decisively as population declines were recognized. After all, while Olympic Peninsula streams have certainly suffered from habitat degradation as a result of logging and impassable culverts, a great deal of the spawning and rearing habit in these systems remains connected and intact. Huge amounts of exceptional upstream habitat is permanently protected within Olympic National Park. The region is free from the large dams that have degraded river ecosystems elsewhere across the Northwest and it has not experienced the scale of development, land use changes, and pollution that affects more populated areas.

With all these advantages, the rivers of the OP should be in much better shape, but long-term status quo management has let wild steelhead numbers continue to slip year after year.

No doubt, historical canneries took an immense toll on the OP’s wild steelhead and salmon populations, but for nearly the last fifty years, co-managers across the Peninsula have primarily operated fisheries under an ethos of Maximum Sustained Yield, a policy that prioritizes impacts and short-term economics instead of sustainability and consistently leads to overexploitation wherever it has been used to guide fisheries.

Image: Lee Geist

Hatcheries were used to mask the losses and continue business-as-usual fisheries, but these programs lacked the reforms, monitoring, and evaluation needed to avoid excessive impacts to wild fish populations.

In 2008, the WDFW developed the Statewide Steelhead Management Plan to help guide fisheries and hatchery operations, but as of today it has yet to be fully implemented.

In the last few years, some efforts have been made to reduce impacts from recreational and tribal fisheries. But the tough decisions required to stop the long-term declines and begin rebuilding wild steelhead populations were always postponed in favor of small steps.

Now, after a year when most rivers on the coast never opened for the winter season and the two watersheds that did – the Hoh and Quillayute – were closed a month early due to low returns, the alarm bells are ringing louder than ever.

The Need for Recovery

Anyone who has fished, floated, or hiked the astounding rivers and streams of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula knows they are a treasure. They have sustained the coast’s Tribes for thousands of years and continue to be a key economic engine for local communities today. Each winter they inspire passionate anglers from across the Northwest – and many from even further away – to visit and fish just for a chance at encountering a powerful wild steelhead during their journey home to spawn.

These fish are far too important to let slip away. After decades of overexploitation and short-sighted management, OP wild steelhead returns are at the lowest levels ever recorded. Climate change is melting glaciers in the Olympic Mountains and warming the Pacific Ocean, compounding the challenges these fish already face. This is the moment to change course while we still can.

The petition process is now in the hands of NMFS. Because of the timelines involved, the ESA petition process won’t directly impact the upcoming winter season. In fact, depending on how long it takes, it might not affect the following one either. But there is no time to wait for federal oversight to force a change of direction. Fishery co-managers must use the tools at their disposal to take meaningful steps to address the factors affecting the Olympic Peninsula’s wild steelhead and begin to truly rebuild their numbers.

To this end, Wild Steelheaders United is participating in the WDFW’s Ad-Hoc Coastal Steelhead Advisory Group (CSAG) to help call for responsible fisheries, increased data collection, hatchery reforms, greater habitat investments, and full implementation of the Statewide Steelhead Management Plan on coastal watersheds, including both the OP and Southwest Washington DPS. The CSAG’s final report and budget request is due to the Washington Legislature by December 1st. Anglers and members of the public can learn more, tune in to public meetings, and offer feedback at the WDFW’s website. Now is the time to have your voice heard.

The budget proviso guiding the CSAG’s work is limited to developing basin-by-basin fishery management plans with stakeholder input. While increased clarity around season-setting and expanded monitoring are much-needed and important first steps, what the Olympic Peninsula’s struggling populations of wild steelhead truly needs is a comprehensive, collaborative plan to focus resources and policy on recovery above all else. The CSAG process must build momentum and concrete steps toward this overarching goal to be considered a success. Otherwise, it will only be another example of short-sighted management schemes failing to meet the challenge at hand.

While we all wait to learn what will happen as the ESA petition moves through the Federal process, its presence is a stark reminder of what is at stake for the Olympic Peninsula’s wild steelhead and the communities that depend upon them. No matter the outcome of the petition process, the path forward must prioritize the recovery of these iconic steelhead runs.

Join WDFW fishery managers at a virtual town hall on October 20 to learn more about preliminary indications of 2021-2022 steelhead returns and discuss the 2022-2023 coastal steelhead season. This is the first of three WDFW-hosted town halls set to take place between now and December 1, the start of the coastal winter steelhead season.